#24 - Intents: Principles and Practice

Addressing the Problem of User Experience for Decentralized Applications

Stanford Blockchain Review

Volume 3, Article No. 4

📚Author: Bridget Harris – Founders Fund

🌟Technical Prerequisite: Moderate

Introduction

From account abstraction to storage proofs, to rollups and bridging, the concept of “intents” has emerged as a transformative force, promising to reshape user experience and transaction efficiency for the growing world of decentralized applications in the crypto space. Within this article, we will explore the concept of an “intent,” explicate how it aims to address the problem of user experience within this article, before diving into how intent is implemented in practice to transform the design architectures of a variety of different verticals, and finally discussing its ramifications on the balance between centralization and decentralization.

The Principles of Intents

Unlike traditional transactions, which involve specific actions executed by users, intents aim to focus on the user's broader goals within predefined parameters. Intents effectively delegate the task to the system, eliminating the need for users to manually navigate fragmented protocols. By not micromanaging every detail of a transaction, intents empower more expressive and efficient transactions while enhancing the user experience. As Paradigm puts it, “By signing and sharing an intent, a user is effectively granting permission to recipients to choose a computational path on their behalf” [1]

Users typically seek the best possible trade prices and often remain indifferent to the underlying platforms involved. This indifference has contributed to the success of platforms like 1inch and the introduction of 1inch Fusion, an early example of intent-driven operations [2]. Intents can be satisfied through various routes, offering flexibility and efficiency compared to the rigid execution paths of traditional transactions.

In some intent infrastructure designs, users express their intents, which are then broadcasted to gossip nodes within a peer-to-peer network. Solvers, often also builders in a fully intent-centric protocol, then compete to execute these intents efficiently and produce valid transactions. A relayer verifies their execution, followed by validation by intent network validators. This decentralized flow ensures intent fulfillment in the most efficient manner possible.

Intents represent an open problem space, and the future of the intent-based user experience remains uncertain. However, the overarching goal is clear: make crypto applications more user-friendly and computationally efficient. A recent Bankless episode with Dan Robinson outlined a high-level user flow, where users sign off-chain messages that are routed through a "MEV black box" to be transformed into on-chain transactions. Intents simplify the process by specifying only the starting and ending points, improving user experience.

An intent offers a user a more streamlined and user-friendly approach compared to an Ethereum (ETH) transaction. Instead of specifying intricate details like gas, slippage, and being restricted to a single decentralized exchange or automated market maker (DEX/AMM), intents simplify the user experience. They require the user to define only a starting point and an ending point, resulting in a more efficient and intuitive interface.

Once the user expresses their intent, the system takes over the task of finding the best price for it. Users merely broadcast their intent as a message, without the need to create a transaction themselves. Subsequently, a variety of solvers are free to fulfill the intent, provided they can demonstrate that they've solved it in the most competitive manner, typically determined by factors like the highest satisfaction gradient. This approach ensures that users receive the best "price" for their intended action. In essence, intents offer a more attractive and flexible alternative for end users compared to traditional on-chain transactions. They can be resolved in multiple ways, often resulting in quicker, cost-effective processes with fewer manual steps.

One applied example of intents can be seen in UniswapX. In UniswapX, Dutch auctions are used for intents where the price is set high and comes down gradually, and the order is filled as soon as it becomes profitable for someone to fill it. The benefits of this in a competitive market, as Dan Robinson points out, are less slippage and a better foundation for order flow auctions.

Uma Roy of Succinct has also provided compelling examples distinguishing between traditional transactions (txs) and intents in her presentation on intents, SUAVE, account abstraction (AA), and cross-chain bridging [4].

Applications of Intent in Practice

Intents hold significant promise across multiple domains, impacting several key areas across the following sectors:

1. Bridges and Rollups

In a recent Bankless episode, Dan Robinson delves into how UniswapX is likely to adopt intents for bridging purposes. Users can express their intent to swap assets like converting USDC on Arbitrum instead of ETH on Ethereum. The proof of fulfilling this intent can then be transmitted through a message-passing bridge to the destination chain. Additionally, Dan suggests that market makers might consider offering more than the standard market price to attract users to funds on a rollup, especially when fulfilling an intent, such as rebalancing for someone exiting.

Unlike traditional bridge designs that custody funds on top of a rollup, UniswapX minimizes risk by exposing only the "swaps currently in flight" to potential attacks. This approach reduces the time funds are vulnerable during swaps, significantly enhancing security and user trust. By abstracting the manual bridging process, intents simplify asset management, resulting in a vastly improved user experience. To fully leverage the potential of intents, users should have access to cross-domain environments, enabling more efficient execution by tapping into various liquidity pools and different technological stacks.

2. Zero Knowledge (Storage) Proofs

With the emergence of L2 and L3 ecosystems, the need for efficient transmission of blockchain state information across these layers is becoming increasingly critical. Zero-knowledge storage proofs offer a solution to this challenge. When a user specifies an intent to transfer assets to a rollup, bridging occurs, and the state of the destination chain is verified using a storage proof. This mechanism ensures that the intent has been correctly fulfilled and that the chain is in the expected state.

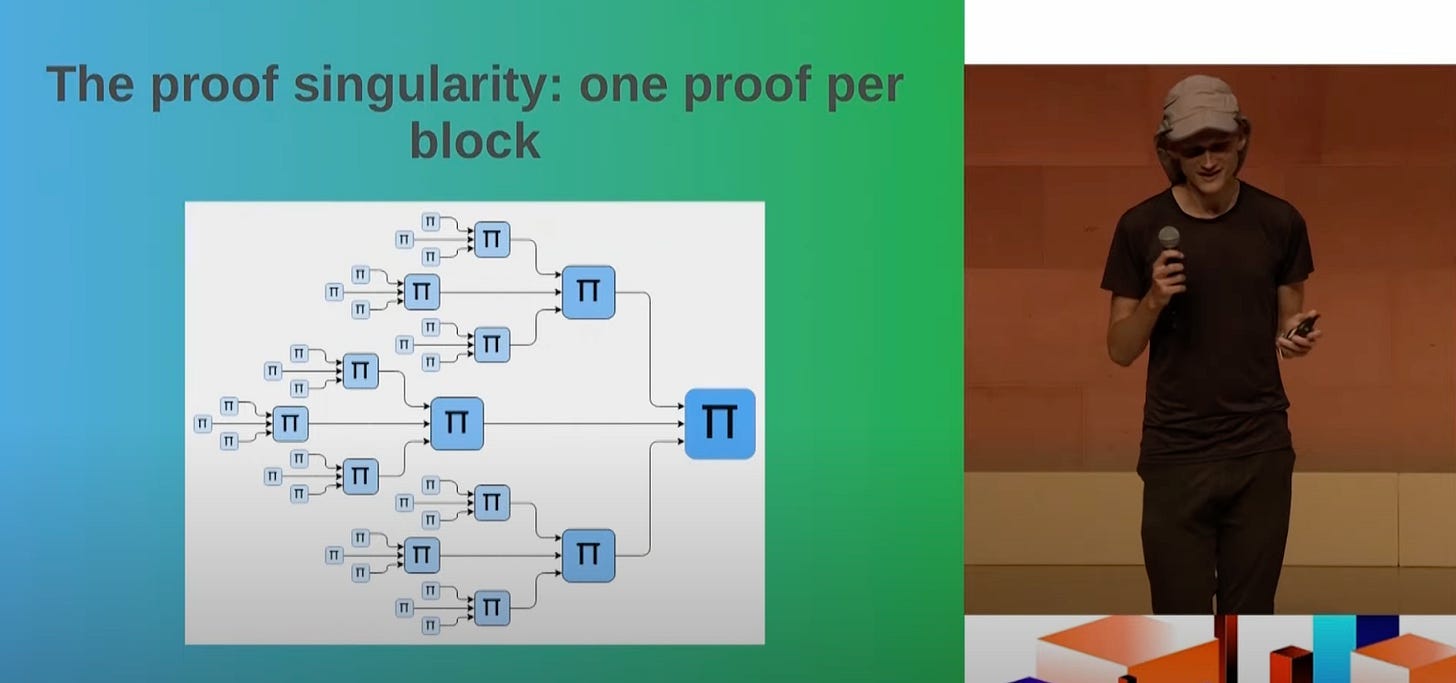

In the future, we might witness the aggregation of fulfilled intents into verifiable storage proofs or aggregated storage proofs to streamline the fulfillment of complex intents. Vitalik Buterin, in a discussion at the EthCC Modular Summit, emphasized the importance of proof aggregation in L2 contexts [5]. This approach helps reduce costs and optimizes the proving process. Innovations like zkTree, introduced by the Polymer Labs team, have opened the door to recursive proving, which could play a pivotal role in enabling zkEVMs, zkRollups, zkBridges, and ZK Storage Proofs.

3. Account Abstraction

Account abstraction is another oft-discussed paradigm shift aiming to enhance user experience (UX). It seeks to upgrade externally owned accounts (EOAs), the current standard for transaction generation, so they can be managed by smart contract wallets or even enable direct functionality within smart contracts to initiate transactions. As intents mature, they may transition from decentralized applications (dApps) to users' smart contract wallets, simplifying the user's role. Stanley He suggests an intent → userOp → bundler process, where intents flow through wallet frontends first [6].

While account abstraction undoubtedly improves UX, users still need to manually discover the most efficient platforms for tasks like swapping, bridging, or liquidity provisioning. Intents aim to eliminate this discovery layer, leaving users with the sole responsibility of specifying their starting and ending states. Furthermore, ERC-4337 introduces designs aimed at preserving decentralization, such as a unified ERC-4337 mempool [7]. This approach reduces the vulnerability of fragmented or smaller pools with diverse bundler policies to censorship and attacks. Ensuring compatibility by adopting a single implementation standard on each bundler minimizes these risks. Several notable projects, including Zerodev, Fun, Stackup, and Rhinestone, are actively contributing to this space.

However, it's worth noting that centralization concerns have been raised regarding intents. Some, such as David Ma of Alliance, argue that intents are challenging to decentralize and are increasingly confined to centralized servers with restricted access rights [8]. Balancing efficiency and decentralization remains a persistent challenge in the crypto space. Despite the allure of streamlined user experiences, certain elements of intents rely on off-chain actors and infrastructure, resulting in significantly lower computation costs compared to regular transactions. This reliance on off-chain components may lead to increased centralization, raising concerns about the concentration of solvers responsible for coordinating intent volume.

Another interesting avenue where intents are making waves is in the context of compliance. Users may soon have the option to choose the most "compliant" route for fulfilling their intents. While this choice can offer regulatory advantages, it introduces a trade-off between cost, speed, and efficiency. Ultimately, it shifts a portion of the regulatory burden onto the user and liquidity providers (LPs), as they make informed decisions about the most suitable route to achieve their goals.

Conclusion

Today, intents are still very much a promising concept in its early stages. But of course, the future comes fast in crypto, and it will be exciting to see how new companies leverage this concept to create new categories and user experiences, whether it be new designs, implementations, or architectures. Nonetheless, the recent emergence and discussions around intents suggests a significant focus on improving overall user experience, particularly for a non-crypto native audience. These measures of abstracting away the “sausage-rolling” of transactions themselves may be crucial factors to drive adoption and improve overall efficiency. In the end, the dynamics between intents, account abstraction, storage proofs, and bridging are still being explored, and how these pieces will work together will be integral to the crypto ecosystem’s maturity [9].

About the Author

Bridget is an Associate at Founders Fund. Previously, she was an Intern at Pantera Capital focusing on early-stage crypto investments. Bridget is also currently a student at Stanford University, majoring in Economics and minoring in Computer Science, and serves as one of the student leaders of Stanford Blockchain Club. You can find more of her writing here.

References

[1] https://www.paradigm.xyz/2023/06/intents

[2] https://messari.io/report/state-of-1inch-q1-2023

[3] DeFi 2.0: How This Changes Everything with Paradigm’s Head of Research, Dan Robinson

[4] Are Intents, SUAVE, Account Abstraction, & Cross-Chain Bridging all the same thing? - Uma Roy

[5] Vitalik: Builders and More Advanced Forms of Aggregation

[7] https://notes.ethereum.org/@yoav/unified-erc-4337-mempool

[8] https://medium.com/alliancedao/intents-are-just-7deaeb4336be

[9] Article edited and adapted from Blueprints by Bridget Harris.