#76 - Cryptography Research Spotlight - An Overview of the LatticeFold Architectural Family

A Conversation with Dan Boneh of Stanford University

Stanford Blockchain Review

Volume 8, Article No. 6

📚 Guest: Prof. Dan Boneh — Stanford University

✍🏻 Author: Yavor — Cryptography at Stanford

⭐️ Technical Prerequisite: Advanced

Introduction

Folding has emerged as a practical way to scale proof systems: instead of proving every step of a large computation independently, or embedding full verifiers inside circuits, folding incrementally compresses many steps into a single accumulator that can be proved succinctly. Conventional schemes largely rely on discrete-log commitments, which are efficient today but not post-quantum and often force large field arithmetic that complicates implementations at scale. LatticeFold takes a different path: it seeks to bring plausible post-quantum security and hardware-friendly arithmetic to folding by building on lattice assumptions and Ajtai-style linear commitments.

In this article, we will first provide a concise crash course on folding, its relationship to zero-knowledge proof systems, and why folding matters for blockchains and rollups. We then develop a technical overview of the LatticeFold family (LatticeFold, LatticeFold+, and Neo), highlighting how their design choices aim to control norm growth while retaining succinctness. Finally, we discuss emerging deployments and an Ethereum-oriented outlook, including the role of folding in aggregating post-quantum signatures and how a Beam-style vision might benefit from these techniques. We would like to acknowledge Dan Boneh and Binyi Chen for authoring LatticeFold and LatticeFold+, and Wilson Nguyen and Srinath Setty for authoring Neo: these works collectively advance lattice-based folding and are the focus of what follows.

1 - A Crash Course on Folding and LatticeFold Preliminaries

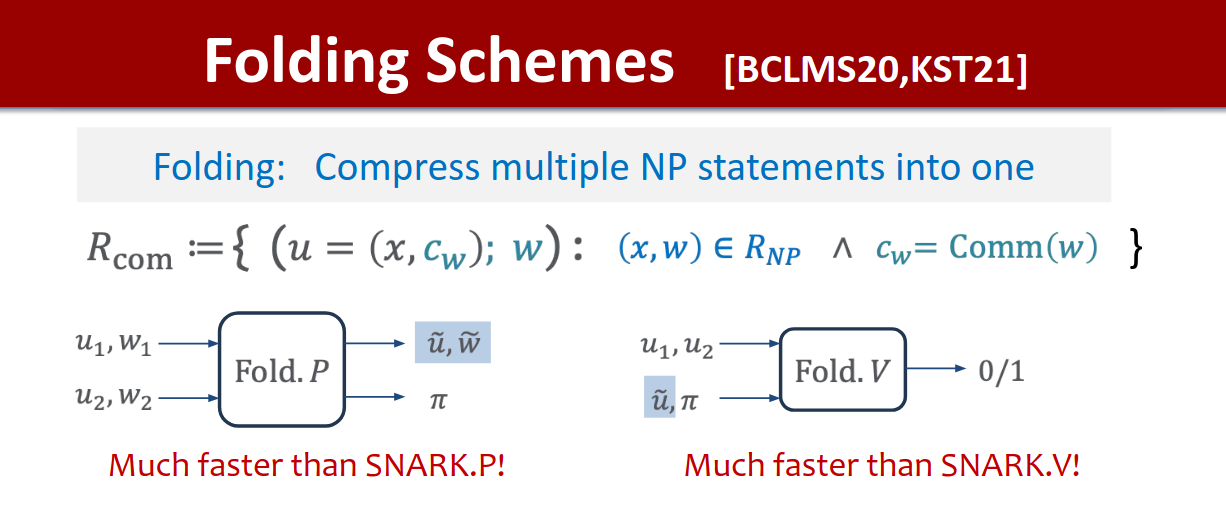

Succinct proof systems (SNARKs) let verifiers check quickly that large computations have been performed accurately, but constructing a single “monolithic” proof of a massive workload can exhaust memory and time. A classic workaround is recursion: break the computation into chunks and prove each chunk, then prove the verifier of the previous proof, and so on. Folding offers a lighter alternative to running full verifiers inside circuits: it merges two instances into one accumulator instance while preserving correctness, so a long sequence of steps can be collapsed and proved once at the end. Formally, a folding scheme gives a reduction of knowledge from R_acc×R_comp to R_acc (R_comp being a single step of a computation, and R_acc relation that accumulates multiple computation steps), enabling many steps to be aggregated into a single statement about R_acc. This viewpoint underlies modern systems like HyperNova for customizable constraint systems (CCS)1.

An overview of folding, both the proving and verification stage, source

As to how this relates to existing zero-knowledge systems, zero-knowledge (ZK) and folding are complementary. ZK governs privacy, where one can prove correctness of a statement while hiding why the statement is correct (the witness)2, whereas folding governs scalability of recursion, that is accumulating many steps into one succinct object to be proved. A pipeline can therefore use folding to compress a long computation trace and then apply any desired SNARK/STARK (with or without ZK) to the final accumulator. This separation is valuable when moving from toy examples to real blockchain workloads (e.g., verifying an entire block or rollup batch).

Folding is important for blockchain systems since onchain and Layer 2 (L2) systems routinely confront proofs over billions of machine instructions or tens of thousands of signatures. Decomposing these tasks into chunks is natural, but repeatedly verifying full proofs inside circuits is expensive. Folding replaces those inner verifiers with simple linear updates to an accumulator, cutting prover memory and often reducing end-to-end proving time. In our interview, the authors emphasize precisely this pipeline: fold a large number of sub-statements (e.g., batches of signatures or trace segments) into one statement and prove that single accumulator at the end.

Most prior folding schemes use additively homomorphic commitments derived from discrete log (e.g., Pedersen). That choice has two ramifications. First, these constructions are not secure against large, fault-tolerant quantum computers. Second, they typically operate over large (≈256-bit) fields and require non-native arithmetic or elliptic-curve operations inside circuits, which inflates prover complexity. These issues show up in comparative analyses against schemes like HyperNova and Protostar3.

Given these problems, LatticeFold enters the picture to replace discrete-log commitments with Ajtai commitments over rings R_q, and bases security on the Module-SIS (MSIS) assumption, which is widely studied and believed post-quantum. Working directly in rings enables arithmetic over small moduli (e.g., 64-bit primes) that align well with modern CPUs/GPUs, avoiding heavy elliptic-curve work and non-native field emulation. The paper’s evaluation targets both low-degree relations (like R1CS) and higher-degree CCS, with an aim of maintaining competitiveness with leading pre-quantum schemes while adding plausible post-quantum security.

Ajtai commitments are succinct and linearly homomorphic, but they are binding only for low-norm messages. Naïvely folding by taking random linear combinations would cause witness norms to grow over many steps, eventually exceeding the binding bound B. This undermines soundness if left unchecked. LatticeFold tackles this by structuring each fold so that witnesses remain provably within a low-norm range throughout long folding chains.

At the high level, LatticeFold organizes each step into three phases, expansion, decomposition, and folding, and buttresses them with a compact range proof built from the sum-check protocol:

Expansion reshapes the per-step relation so the accumulator and the next step can be combined without introducing problematic cross terms. For high-degree CCS, a preliminary linearization via sum-check avoids multiplicative blowups.

Decomposition writes each committed vector in a small base b so that it splits into several low-norm “digits.” Instead of combining two large-norm vectors directly, the scheme works with many small-norm fragments, making subsequent linear combinations safe with respect to the required norm bound.

Folding then aggregates those fragments using small-norm challenges drawn from a carefully chosen sampling set, preserving the low-norm invariant of the accumulator. A sum-check-based range proof certifies that all fragments truly lie in the claimed range, ensuring extractability remains compatible with the Ajtai binding guarantee.

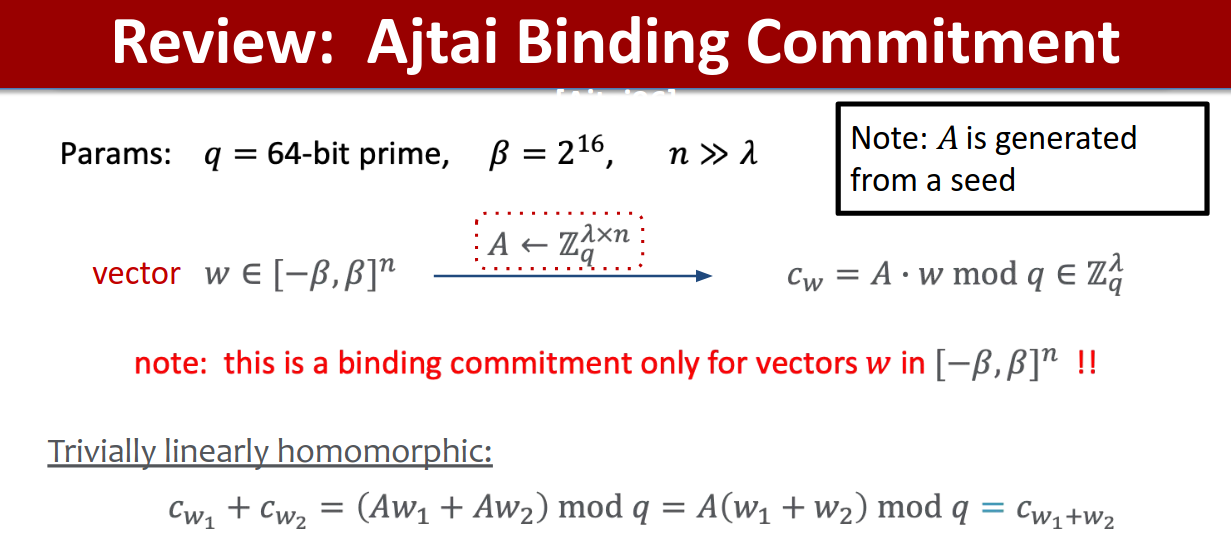

At a conceptual level, readers can think of Ajtai commitments as matrix–vector products in a ring: public parameters define a random rectangular matrix A over R_q, and committing to a vector x amounts to computing Ax. Linearity gives the homomorphism needed for folding, while MSIS underpins binding for low-norm openings. The combinatorial work of LatticeFold is to make sure the running “sum” of many steps never escapes the allowed range, even when we fold thousands of times.

Because LatticeFold operates over 64-bit moduli, it aligns with commodity hardware and lends itself to GPU acceleration, an angle the interview highlights explicitly. This hardware fit is particularly relevant for blockchain pipelines that must process high-volume batches under tight latency and cost constraints. Moreover, folding can play a central role in Ethereum’s prospective migration to post-quantum signatures: many hash-based signatures could be folded into a single accumulator and then proved succinctly, providing the aggregation properties that BLS gives today in the pre-quantum world. These themes, GPU friendliness and signature aggregation, emerge repeatedly in ongoing experimentation the authors mention.

We have sketched folding’s motivation and the LatticeFold intuition without the algebra. In the next section, we will unpack how LatticeFold, LatticeFold+, and Neo instantiate these ideas, how expansion, decomposition, and folding are realized over Ajtai commitments; how sum-check certifies range constraints; and how higher-degree CCS is linearized for efficient accumulation.

2 - A Technical Deep Dive into the LatticeFold Architecture

In order to cover the LatticeFold algorithm completely, we must first precisely describe various cryptographic ideas that will be used for the larger scheme. The key contribution of LatticeFold is that it swaps the usual discrete-log (elliptic-curve) commitments used by prior folding schemes for Ajtai commitments built from lattices. Concretely, the public key is a random matrix , and to commit to a vector , one must compute . This commitment is binding (one can’t open it two different ways) as long as the committed vector is “small”, i.e., its entries have bounded size (more on “size” below). The binding guarantee relies on the Module-SIS (MSIS) hardness assumption, which is believed to be post-quantum secure.

A review of Ajtai commitments, source

If one wished to read the LatticeFold paper in detail, one would repeatedly see the word “norm” and its importance for it to be small. What does this mean? When we say an entry is “small,” we measure it with the ℓ∞ norm: this should be thought of as “the largest absolute coefficient you see.” Here, a “coefficient” means the integer coefficients of a ring element (a polynomial modulo X_d + 1) after reducing into [−q/2,q/2). For a vector of ring elements, ∥x∥∞ is the largest absolute coefficient appearing anywhere in the vector. Ajtai commitments are binding for vectors whose ℓ∞ norm is below a threshold B. If, during folding, our vectors grow beyond B, binding can break, and therefore LatticeFold is engineered to keep norms small at every step.

Additionally, LatticeFold works over a cyclotomic ring R=Z[X]/(Xd+1) and its mod-q version

Rq=R/qR. The relevance is that these rings (a set of elements where one can perform addition and multiplication) support fast number-theoretic transforms and are standard in lattice cryptography. Using such rings also makes 64-bit arithmetic feasible in practice.

Furthermore, both R1CS and CCS (terms used frequently in LatticeFold and other literature relating to folding) are ways to encode a computation trace (such as a program execution) as algebraic constraints. This “arithmetization” is what proof systems operate on, as they lend themselves to various algebraic cryptographic operations. R1CS uses only quadratic (degree-2) constraints, whereas CCS (customizable constraint systems) allows higher-degree gates, which can be more compact for some workloads. Folding schemes like HyperNova and LatticeFold target CCS so they can handle both low- and high-degree circuits efficiently.

Given all of this, LatticeFold turns each fold into three steps: expansion, then decomposition, then finally folding. There is also a lightweight range proof ensuring every committed vector really is low-norm.

Expansion: The purpose of this step is to make folding algebraically simple: before we combine “the accumulator” with “the next step,” we rewrite the step’s CCS relation into a linearized form that is easy to add up. This mirrors HyperNova’s linearization (done there over fields), adapted here to rings. One can think of it as moving to a representation where “adding instances” corresponds to “adding their commitments and claims” without creating hard cross-terms.

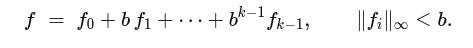

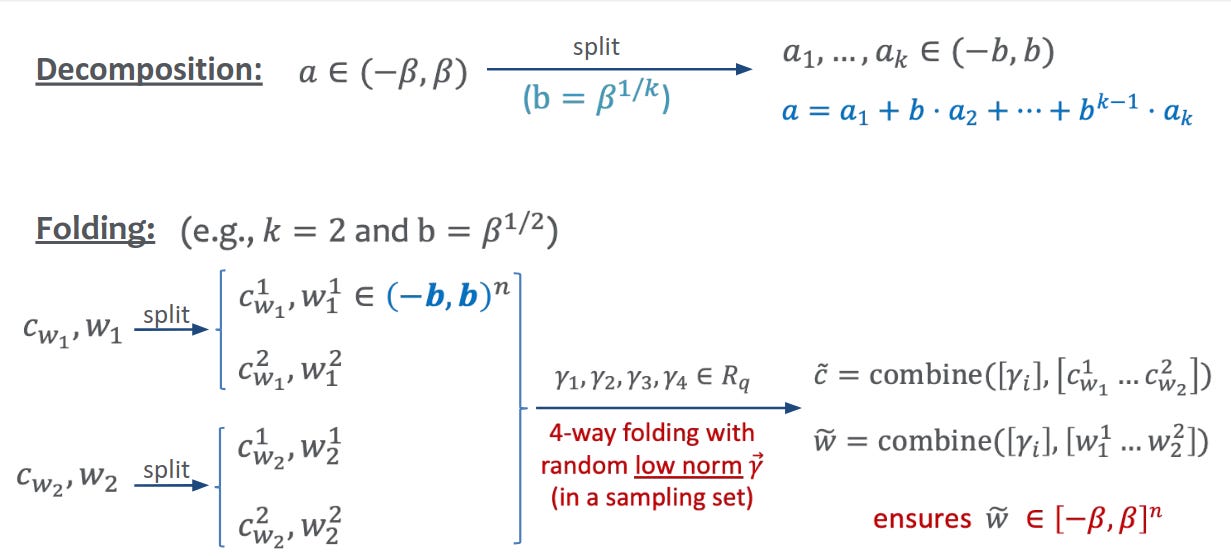

Decomposition: Here, we wish to break apart big numbers into smaller, more manageable digits. If we combined two witnesses directly, their entries would grow and eventually exceed the binding bound B. LatticeFold avoids this by writing each vector f in base b so all pieces are tiny:

Here, b is a small base (e.g., 2 or 4), k is the number of digits, and B=b^k is the overall bound we’re willing to allow. After decomposing two witnesses, we have 2k low-norm fragments instead of two large-norm vectors. (A standard “gadget” map makes this decomposition deterministic and efficient).

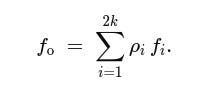

Folding: Finally, we wish to combine many small pieces safely. To fold, the verifier samples small-norm challenges ρ_1,…,ρ_2k from a strong sampling set, a set of ring elements whose pairwise differences are invertible and whose coefficients are tiny enough that multiplying by them doesn’t blow up norms too much. The prover forms one folded witness:

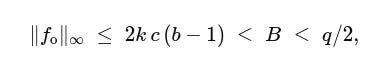

Because each f_i has tiny entries and each ρ_i has tiny coefficients, the key bound holds:

where c is a constant capturing the “expansion factor” of the challenge set (how much norms can grow when we multiply by a challenge). This inequality says the folded witness still lives inside the binding range, so we can keep folding. The “invertible differences” property guarantees the knowledge extractor (used in the security proof) can safely undo combinations.

A precise diagram of the Decomposition and Folding stages (a_1, .. , a_k are equivalent to f_0, … f_k-1), source

All this only works if the prover proves its digits f_i are genuinely small and within the promised range (e.g., [−b,b]). LatticeFold encodes “u is in range” as a small polynomial identity whose zeros are exactly the allowed values, then uses sum-check over the ring to verify it for all positions at once. Sum-check is a classic subprotocol that lets a verifier check “the sum of many polynomial evaluations equals T” by interacting over a few rounds with much smaller polynomials. In short, one proves that the pieces are small, then small challenges keep them small when combined.

As to how the parameters b and k are selected, a tiny base (2 or 4) is used in practice for b. Larger bases make range proofs heavier without enough payoff. k is chosen so that the safety inequality 2k c (b−1) < B < q/2 holds comfortably, where the left side is “worst-case growth per fold,” and the right side keeps it below the modulus’s halfway point (a standard safety margin). Larger k increases B exponentially but makes decomposition produce more pieces per fold, thus implementations tune k for their workload and challenge-set constant c.

Why does the above scheme work? Well, the Ajtai commitment is linear (which means A(x+y)=Ax+Ay) and binding for low-norm messages under MSIS. This linear structure allows for commitments to be added during folding, and binding is preserved by staying below B. Decomposition works because the extractor for security reasons may need to divide by a random difference like (ρi−ρj). Doing everything at the tiny-digit level ensures that even after algebraic manipulations, the extracted pieces remain within range.

As monumental as the LatticeFold paper is, subsequent iterations and modifications have come out that have presented updates and optimizations. One such paper is LatticeFold+, which addresses the fact that LatticeFold’s heaviest subroutine is the range proof (checking that all digits lie in range), which in the original protocol used bit-decomposition and many commitments. LatticeFold+ replaces this with a purely algebraic range proof:

The prover commits to monomials m_i=X^(f_i) (one per entry) and proves two things: (i) each m_i is indeed a monomial, and (ii) a simple algebraic relation holds between mi and the original fi. From these two facts, it follows that every fi lies in (−d/2,d/2). This avoids committing to bits entirely and dramatically shrinks the work.

To keep transcripts short when vectors have d coefficient “slices,” LatticeFold+ introduces double commitments, “commitments of commitments”, so the verifier receives one compact object instead of d separate commitments. A commitment transformation step (checked by sum-check) then maps this object back into an ordinary linear commitment that the folding machinery can handle. Net effect: shorter proofs and a simpler recursive verifier.

Structurally, LatticeFold+ folds L>2 linear instances into one instance with a temporarily larger bound B^2, then uses a high/low split (a mini-decomposition) to return to two instances with bound B. This two-step trick achieves lower overall cost than doing many bit-based range proofs.

In short, LatticeFold+ keeps the LatticeFold backbone but removes the bit-decomposition tax and compresses the recursion layer. That means faster provers and a smaller verifier circuit in practice4.

Neo, another paper that builds on LatticeFold, keeps the lattice security foundation but designs the commitments and reductions so that folding can run over small prime fields (e.g., Mersenne-61 or Goldilocks) and, crucially, the cost to commit scales with bit-width (“pay-per-bit”), similar to what Pedersen/KZG do, something LatticeFold’s ring embedding did not achieve5.

Why pay-per-bit matters: Many witnesses are mostly small values or bits (flags, Merkle checks). Neo’s commitment maps field vectors into ring elements so that multiplying by a binary “mask” only adds a few columns, hence cost scales with the number of 1-bits. The mapping retains the linearity needed for folding evaluation claims.

Strong sampling and invertibility: As in LatticeFold, challenges come from a strong sampling set whose differences are invertible; Neo leverages explicit low-norm invertibility bounds to pick these safely in small fields.

Three reductions, field-first. Neo composes: (i) CCS → (partial) evaluations via sum-check; (ii) random linear combination of k+1 claims into one B=bk claim; (iii) decomposition to keep norms under the binding threshold. It’s the same general algorithm (linearize, combine, keep small) but engineered for small-field arithmetic and “pay-per-bit” commitments.

Taken together: LatticeFold gives the first lattice-based folding with disciplined norm control over rings, LatticeFold+ streamlines range proofs and shrinks recursion artifacts, and Neo unlocks small-field performance and pay-per-bit costs while staying plausibly post-quantum. The architectural through-line, decompose into small pieces, combine with small challenges, certify with sum-check, is what makes the whole family practical.

3 – Latticefold’s deployments and its future with Etherium

Early implementations are underway. In our interview, the authors noted that NetherMind is actively prototyping both LatticeFold and LatticeFold+, with performance numbers expected from that effort; other groups are experimenting as well. While results are still being finalized, the direction of travel is clear: evaluate LatticeFold’s recursion in real proving pipelines and compare it to pre-quantum baselines.

Two engineering properties make these prototypes attractive. First, LatticeFold works over small (≈64-bit) moduli and a single module structure, avoiding heavy elliptic-curve arithmetic and non-native field emulation inside the accumulator relation. That tends to simplify implementations relative to group-based folding. Second, 64-bit rings map cleanly to GPUs, and even to prospective FHE accelerators that operate over similar number-theoretic rings, so hardware built for FHE may also accelerate lattice-based folding. These factors are explicitly highlighted by the authors as reasons implementers expect good constant factors once code paths are tuned.

As to what earlier adopters are likely to try first, short-term experiments are natural where (i) workloads are embarrassingly parallel (e.g., batched signature checks, Merkle membership checks, or trace segments), and (ii) the folding verifier must stay small for recursion. The LatticeFold paper reports performance that is comparable to HyperNova for degree-2 relations and better for high-degree CCS, suggesting that CCS-heavy zkVM circuits, rollup state transitions, or hash-heavy workloads may be a good initial fit. Fold many sub-instances to a single accumulator; then produce one succinct proof at the end.

There are many possible future research directions, but as is described by the authors, LatticeFold+ shows that purely algebraic range proofs and a commitment-to-commitments “compression” step can shorten proofs and reduce the recursive verifier (fewer hashes in the Fiat–Shamir circuit), aiming for a faster prover than HyperNova while retaining plausible post-quantum security. The paper emphasizes that folding proofs act as recursive witnesses, they do not appear on chain, so shrinking them chiefly reduces the recursive verifier cost, not the final on-chain proof size. The authors also flag two open avenues: (1) re-working the analysis and subprotocols in ℓ₂ (which can improve MSIS parameters), and (2) generalizing beyond prime moduli (e.g., powers of two) for implementability

Neo pushes in a complementary direction: preserve lattice assumptions but fold over small prime fields (e.g., Mersenne-61 or Goldilocks), avoid costly cyclotomic-ring sum-checks, and restore “pay-per-bit” commitment costs so committing to bits is far cheaper than to 64-bit words. That unlocks fast arithmetic and a single sum-check invocation, two practical wins for real systems, while staying plausibly post-quantum.

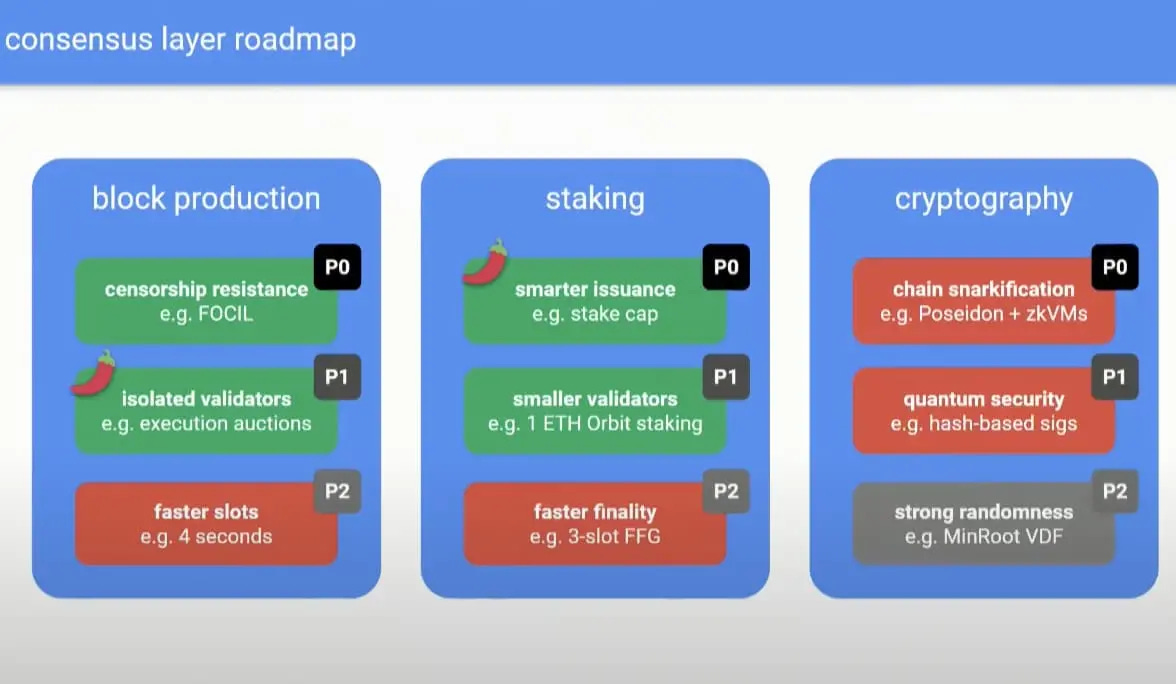

Finally, it is critical to discuss Etherium’s BeamChain vision and how LatticeFold might contribute to this ecosystem. At a high level, BeamChain is a conceptual direction for Ethereum that simplifies the consensus layer and moves succinct proofs to the center of the protocol. A concrete driver is post-quantum migration: Ethereum today relies on BLS for validator signatures (aggregation and thresholding are essential to PoS), but there is no drop-in post-quantum scheme with the same aggregation properties. The working plan is to adopt hash-based signatures for security, and then recover aggregation-like compression by SNARK-ifying many signatures into a single succinct proof6. The authors underscore that this can be done monolithically, that is fold first, then prove once. Folding promises to reduce prover memory and latency by replacing “verifying a full proof inside a circuit” with lightweight accumulator updates over the epoch.

An overview of the BeamChain Vision, source

For BeamChain-style consensus, validators produce large batches of post-quantum signatures (e.g., per-slot attestations). Instead of building one giant monolithic proof per slot or per epoch, the pipeline can: (1) verify a chunk of signatures, (2) fold the resulting statements into the epoch’s accumulator using Ajtai commitments and small-norm challenges, and (3) repeat across slots; at epoch end, produce one succinct proof of the accumulator’s validity. Folding keeps the recursive verifier small and uniform, and the arithmetic (64-bit rings) maps to commodity hardware and GPUs. In effect, LatticeFold gives consensus designers a recursion substrate that is plausibly post-quantum secure and tuned for high-throughput batch workloads.

In our interview, the authors suggested evaluating a folding-first approach against a STARK-first or monolithic baseline along common KPIs: proof size (for on-chain verification and propagation), end-to-end latency (time to finality), and decentralization (hardware requirements for home validators and community provers). Folding contributes by lowering prover memory and allowing work to be pipelined through slots into a single epoch-level statement. The on-chain interface would still verify a single succinct proof; folding lives off-chain as part of the recursive construction, so the on-chain verifier does not need to check intermediate folding proofs. (LatticeFold+ explicitly notes that folding proofs are recursive witnesses, not part of the final proof object.)

Hash-based signatures are robust and simple, but they are large and numerous. Folding converts “verify N big signatures” into “update an accumulator N times,” which is fundamentally cheaper to express than re-verifying a full proof N times in-circuit. The authors argue this may “dramatically speed things up,” pending experimental confirmation from NetherMind and others. In other words, if Ethereum’s post-quantum path is “hash-based signatures + succinct aggregation,” a lattice-based folding substrate provides the missing accumulation primitive with post-quantum plausibility.

The 64-bit arithmetic in LatticeFold is a pragmatic match for GPU vector units; implementers are already targeting GPU folding. Longer-term, specialized FHE ASICs (designed for similar ring operations) could double as folding accelerators, aligning consensus-critical proving with a broader hardware roadmap. That is an unusual and promising alignment: investment in FHE hardware can amortize to proving infrastructure.

LatticeFold+ trims the recursive verifier and speeds the prover via algebraic range proofs and double-commitment compression. In a BeamChain pipeline this reduces the cost of the recursion layer, making per-slot updates cheaper and shrinking the accumulator circuit budget. Neo complements this by allowing folding directly over fast small fields (M61, Goldilocks), restoring pay-per-bit commitment costs and eliminating the 10–100× overheads associated with cyclotomic ring sum-checks, useful when the workload is bit-heavy (hashes, flags, Merkle checks). Together, they suggest a migration path from “LatticeFold as first prototype” to “LatticeFold+ for practical recursion” to “Neo for small-field, bit-efficient deployments.”

Some protocol engineering remains. Neo documents constraints on LatticeFold’s ring choices (full splitting can harm security), motivating its shift to small fields; compatibility and parameterization across clients need careful study. More broadly, the community will want head-to-head measurements of end-to-end latency, GPU utilization, and operator costs under production loads, and a clear story for proving service decentralization. Finally, formalizing ℓ₂-based analyses and supporting non-prime moduli (both flagged by LatticeFold+) would broaden parameter choices and simplify implementations.

BeamChain’s post-quantum vision, hash-based signatures plus succinct aggregation, pairs naturally with lattice-based folding. LatticeFold provides the core reduction-of-knowledge machinery over 64-bit rings; LatticeFold+ makes the recursion layer slimmer and faster; Neo opens small-field routes with pay-per-bit commitments. If experiments from NetherMind and others validate the anticipated gains, Ethereum can plausibly adopt a folding-first accumulation layer for post-quantum consensus, with a familiar on-chain footprint (one succinct proof per epoch) and a flexible, hardware-friendly off-chain pipeline.

Conclusion

Folding is emerging as the practical engine of scalable, recursive proving: it aggregates long computations into a compact accumulator, leaving privacy to the underlying proof system and shifting the performance focus to efficient, repeatable updates. LatticeFold shows how to realize this paradigm on lattice assumptions: replacing discrete-log commitments with Ajtai commitments, operating over 64-bit rings, and, crucially, controlling norm growth via base-b decomposition, carefully sampled challenges, and sum-check–based range arguments. LatticeFold+ refines the recursion layer with algebraic range proofs and double-commitment compression, substantially reducing prover work and the size of the recursive verifier. Neo pushes further by enabling small-field, “pay-per-bit” commitments while preserving a post-quantum foundation.

These advances are not merely theoretical. Early implementations are exploring performance on real pipelines, and the Ethereum-facing BeamChain vision highlights a compelling application: aggregating large volumes of post-quantum signatures by folding per-slot statements into a single epoch-level proof. The hardware fit, 64-bit arithmetic and GPU-friendliness, strengthens the case for practical adoption.

We would like to acknowledge Dan Boneh and Binyi Chen for LatticeFold and LatticeFold+, and Wilson Nguyen and Srinath Setty for Neo. Together, these works chart a credible path from post-quantum security assumptions to deployable, high-throughput recursion, an essential ingredient for next-generation rollups, consensus, and verifiable computation at blockchain scale.

About the Interviewees

Prof. Dan Boneh

Professor Boneh heads the applied cryptography group and co-directs the computer security lab. Professor Boneh’s research focuses on applications of cryptography to computer security. His work includes cryptosystems with novel properties, web security, security for mobile devices, and cryptanalysis. He is the author of over a hundred publications in the field and is a Packard and Alfred P. Sloan fellow. He is a recipient of the 2014 ACM prize and the 2013 Godel prize. In 2011 Dr. Boneh received the Ishii award for industry education innovation. Professor Boneh received his Ph.D from Princeton University and joined Stanford in 1997.

Yavor Litchev

Yavor is an undergrad at Stanford pursuing a degree in computer science with a focus on cybersecurity and cryptography. He has previously engaged in research projects relating to secure machine learning and digital signatures with more flexible access structures at MIT PRIMES. More recently, he is researching secure systems and program execution using software fault isolation through the CURIS program. He is currently the cryptography research lead and Financial Officer for the Stanford Blockchain Club.

LatticeFold: https://eprint.iacr.org/2024/257

LatticeFold+: https://eprint.iacr.org/2025/247

❤️