#73 - Unpacking MonadBFT: Fast, Responsive, Fork-Resistant, Streamlined Consensus

Stanford Blockchain Review

Volume 8, Article No. 3

📚 Author: Michael Li — Monad

🌟 Technical Prerequisite: Intermediate

Blockchain enforces strict global consensus, which means everyone running the network, anywhere in the world, agrees on the same set of objective outcomes.

But how does a distributed system reach agreement even when some participants are lying, offline, or actively trying to subvert the process?

This is where consensus protocol comes in. It is a set of rules that allow a network of independent and potentially dishonest participants to agree on the order and contents of transactions.

Once you have this ‘strict global consensus’, blockchain unlocks wonderful properties like digital property rights, monetary hardness, and social scalability. But all of that rests on a protocol’s ability to maintain safety (no two conflicting blocks are finalized) and liveness (the network keeps making progress).

This article explores MonadBFT, which builds on the HotStuff lineage. We’ll examine how it solves persistent issues like tail-forking, achieves speculative finality in a single round, and enables optimistic responsiveness. Together, these properties make MonadBFT a foundational advancement for high-performance blockchains.

A brief recap on past consensus mechanisms

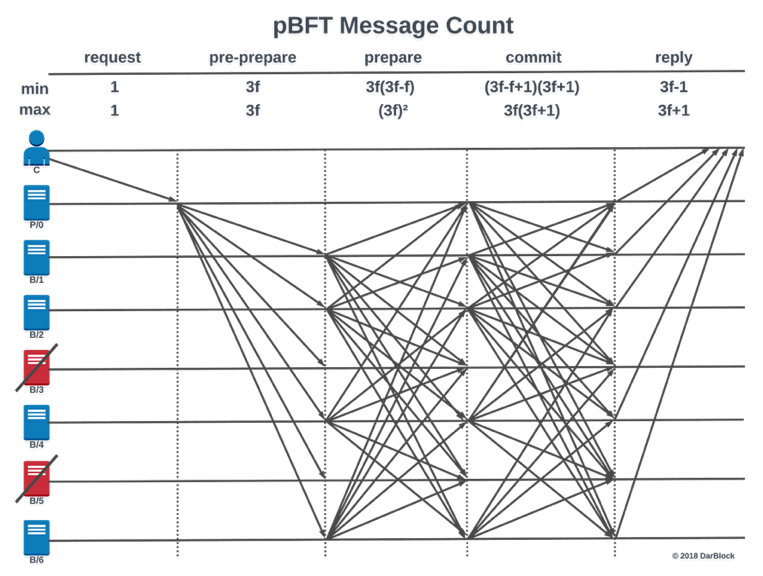

The field of consensus mechanisms has evolved over decades. Early protocols like PBFT [1] (Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance) showed that agreement was possible even when up to f nodes (out of 3f+1) were malicious. These classical designs work by electing a leader who coordinates multiple rounds of voting among validators.

In each phase (e.g. pre-prepare, prepare, commit, reply), every validator must communicate with every other validator. This leads to quadratic message complexity (a full mesh of communication): if there are n validators, you need roughly n² messages per round. That’s manageable in small networks but becomes unworkable as the validator set grows.

Source: https://medium.com/coinmonks/pbft-understanding-the-algorithm-b7a7869650ae

Quadratic messaging is inefficient. In a network with 100 validators, you have to process tens of thousands of messages per round. For global, permissionless systems, that’s too heavy. As a result, early BFT protocols like PBFT and Tendermint were often deployed in permissioned systems or small validator sets where performance constraints were tolerable.

To scale BFT for permissionless environments, newer protocols opt for linear communication: every validator talks only to the leader, reducing message complexity from n² to n.

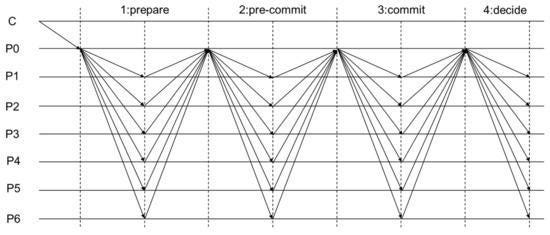

Hotstuff was first introduced in 2018 and it pushed BFT consensus forward by introducing a streamlined, leader-centric communication pattern.

HotStuff features linear communication. Instead of the quadratic explosion of messages in PBFT, in HotStuff all validators just send their vote to the next leader. That leader combines them into a single, compact proof called a Quorum Certificate (QC). The QC is proof to anyone observing it that ‘most nodes agreed with the proposal.’ Unlike PBFT where everyone checks with everyone (causing messaging overload), HotStuff is ‘vote once, bundle once’, meaning the network stays fast even as it grows.

Notice the fan-out fan in structure and difference with the ‘mesh’ pattern of PBFT

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/24/16/5417

Further, HotStuff may be pipelined for additional efficiency. In the original HotStuff protocol, the same validator serves as the leader through each round of communication until the block is finalized, and only one block is worked on at a time. In Pipelined HotStuff, each round of communication has a new leader, who is responsible both for assembling/propagating the Quorum Certificate from the previous round’s votes and also for proposing a new block.

In Pipelined HotStuff, instead of waiting for a single leader to do everything needed to finalize a block, each leader in a sequence plays a role. Leader 1 proposes a block, then Leader 2 assembles and shares a QC for Leader 1’s block while also proposing a new block, and so on. This setup forms a chain, where each new leader helps confirm the block that came before. Pipelining really just means overlapping these steps (i.e. while one block is being finalized, the next is already being proposed).

In short, HotStuff-based protocols achieved much better decentralization and performance: they can include more validators and finalize blocks with fewer messages and rounds. These properties have made HotStuff the template for many modern PoS consensus implementations. However, as we’ll see next, the pipelined design also introduces a subtle vulnerability that wasn’t immediately apparent.

The Problem of Tail-Forking

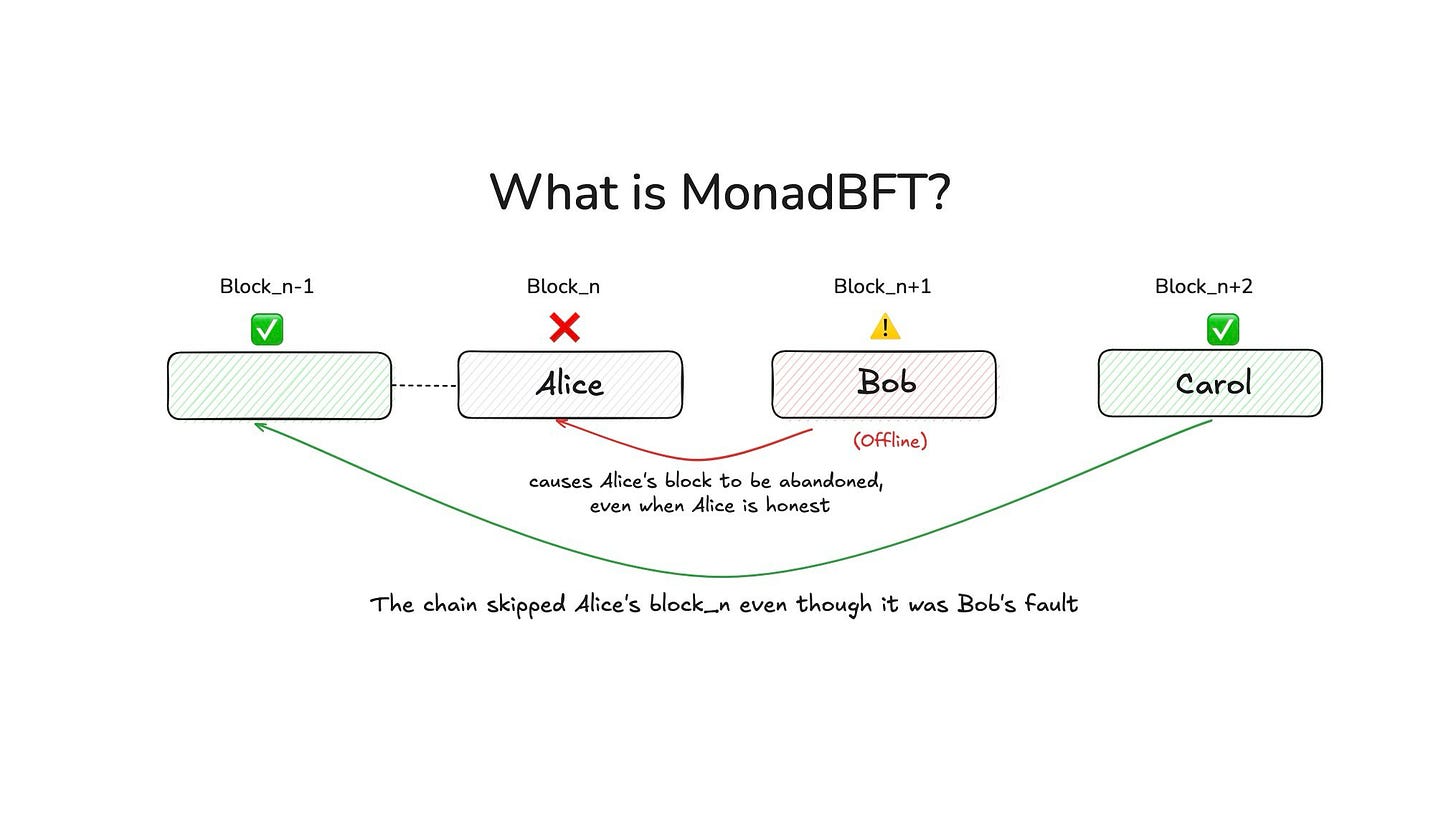

While HotStuff (more specifically pipelined HotStuff) addressed scalability issues, new challenges come with its design. A major issue for pipelined protocols is tail forking.

Tail forking can be understood as a chain reorganization at the ‘tail’ of the chain. It occurs when a block that is valid and correctly propagated to other validators should become a part of the chain (it received the required votes) but ends up getting abandoned (orphaned) due to the behavior of the next leader.

Essentially, a block is proposed and validated by a supermajority but still fails to commit and is replaced by a different block at the same block height (very unfair right?!).

Why would this happen? In pipelined HotStuff, each leader has two jobs: A. propose a new block, and B. gather votes (form a QC) for the previous leader’s block.

For example, suppose validator Alice proposes block B_n and a supermajority of validators voted for it (enough to eventually form a QC). Normally, the next leader Bob (working on block B_n+1) should include that QC in his proposal.

But if Bob is offline or intentionally misses his slot, the QC for B_n won’t be propagated, and B_n will be abandoned.

Why does tail forking matter?

Tail-forking is 1) economically unfair and 2) potentially dangerous for liveness.

First is the issue of lost rewards: When a block is abandoned, the proposer loses any block rewards or fees. In our example, Alice gets nothing because Bob failed to finalize her block. This creates unfair incentives—malicious leaders can sabotage others’ rewards. Even honest validators might get penalized due to bad luck or misbehavior, discouraging participation or encouraging collusion.

Second is the issue of MEV exploitation. If Alice’s block contains valuable arbitrage, Bob can collude with Carol to discard it and insert a new block capturing the same MEV. This kind of cross-slot reordering attack undermines fairness and encourages validator collusion.

Third is the issue of UX and finality guarantees. BFT protocols promise deterministic finality, but tail-forking breaks this at the chain tip. Some dapps rely on pre-finality execution to reduce latency. If a voted block is dropped, users might see state reversals which means missing trades, incorrect balances, or broken game logic.

Fourth is cascading failure. While a one-block delay is the most common, repeated forks by multiple faulty leaders can stall the chain entirely until someone commits a block that sticks.

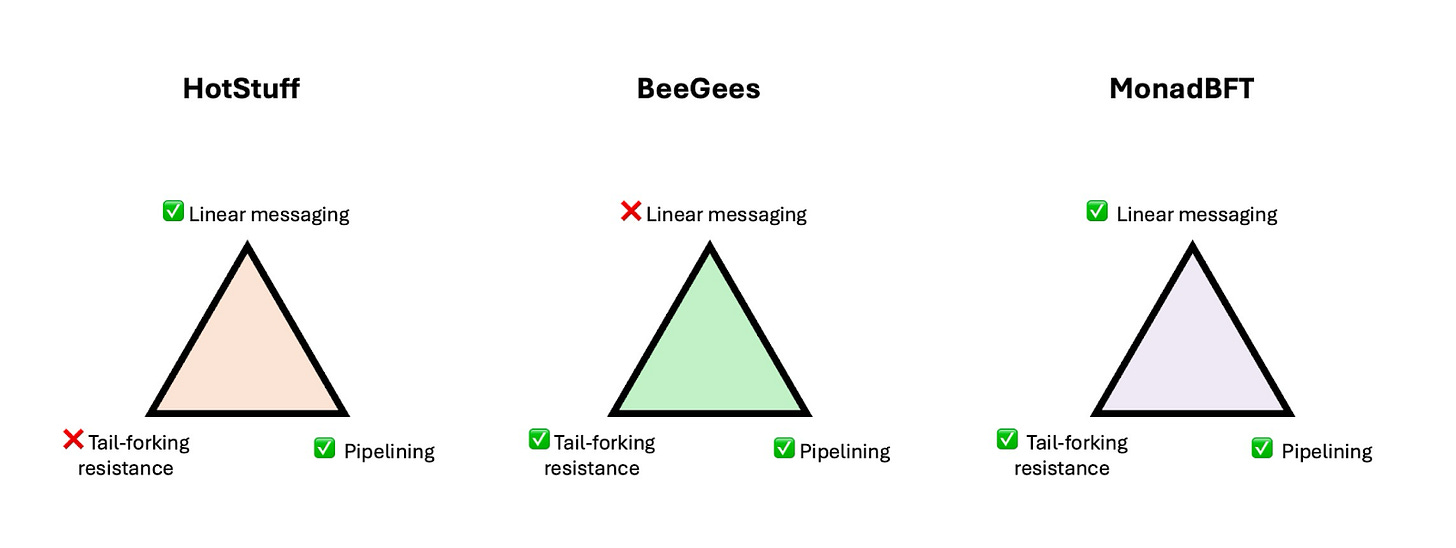

Tail forking is a real, not just theoretical, issue. All pre-MonadBFT pipelined BFT protocols are vulnerable to it, since they rely on the next leader to finalize the previous block. Some solutions exist, like BeeGees [2], but they reintroduce costly trade-offs such as quadratic communication.

What is MonadBFT?

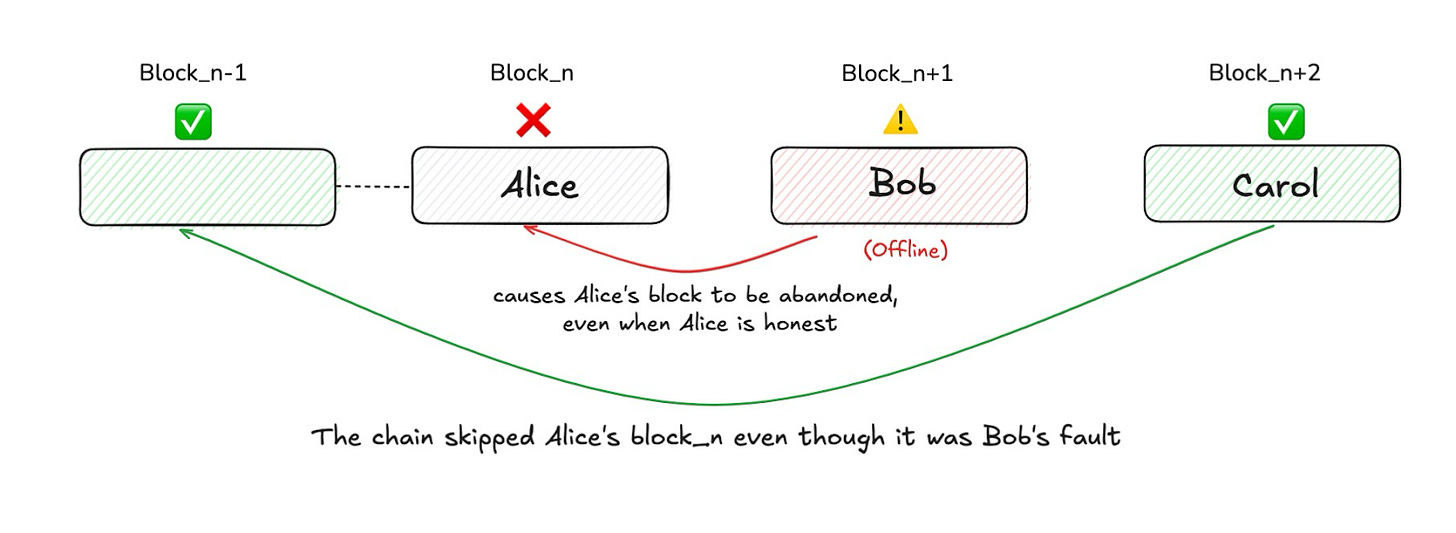

MonadBFT was created to directly address tail-forking vulnerability while preserving the performance gains. It builds on the HotStuff framework, which means 1) having rotating leaders, 2) pipelined commits, and 3) linear messaging, but introduces mechanisms to improve safety and liveness without sacrificing throughput.

The first priority for MonadBFT is to guarantee that any block proposed by an honest leader (that gathered a supermajority vote) will not get abandoned. The desired outcome here is that if a block gets a supermajority support, the protocol ensures that block will eventually be finalized and included in the chain (cannot be orphaned or skipped). The mechanism to enforce this is twofold: 1) mandatory reproposal and 2) the No-Endorsement Certificate (NEC).

Re-proposals

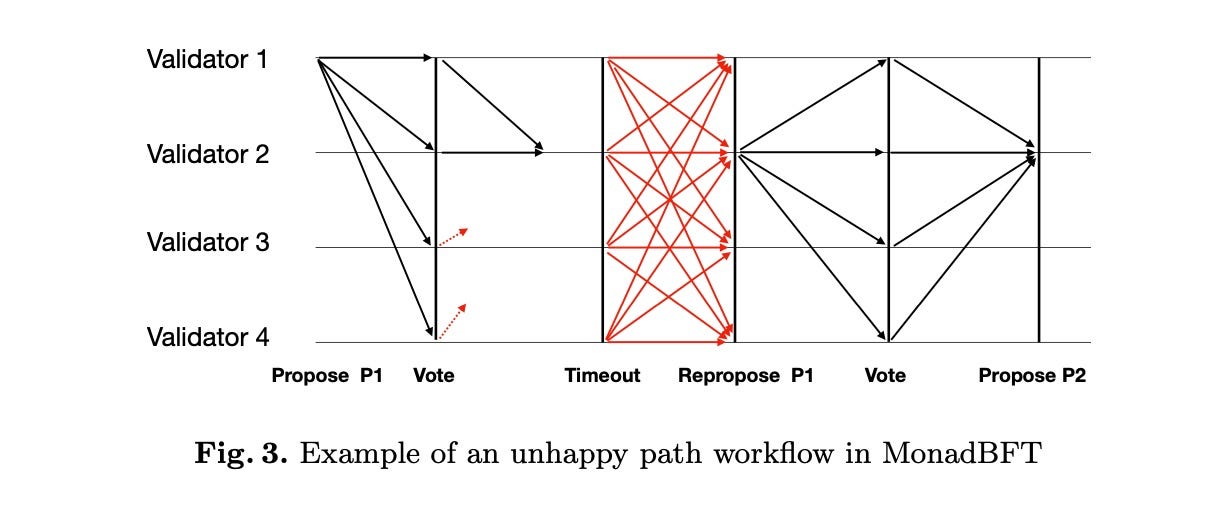

In a BFT protocol, time is divided into rounds called “views.” Each view has a designated leader responsible for proposing a new block. If that leader fails, which means they 1) did not send a proposal on time or 2) sent an invalid one, the protocol moves to the next view with a new leader. MonadBFT includes a mechanism that ensures no honest block gets abandoned during this transition.

When the current leader fails, validators trigger a view change by broadcasting a signed message indicating that the round has timed out. Importantly, these messages also include some other information beyond just ‘hey there’s a failure’.

Each one must also include a reference to the most recent block that the validator saw and voted for. Think of it as saying: “I attest to not receiving a proper proposal this round, and here’s the latest block I have seen.”

The new leader then collects these timeout messages from a supermajority of validators (2f+1) of them and combines them into what’s called a Timeout Certificate (TC). The TC provides a snapshot of the best-known blocks across the network when the last round failed. Among these, the leader identifies the most advanced block (based on block height or view number, which is labelled “high_tip”).

MonadBFT requires the new leader’s proposal to include a TC formed from 2f+1 validators’ timeout messages, and to re-propose the highest-known pending block referenced in the TC , giving that block another chance to gather enough votes and be finalized. Why? Recall our intention earlier. This will ensure that blocks which were nearly finalized before the failure don’t simply vanish.

To illustrate: suppose Alice is the leader in view 5 and proposes a valid block that receives many votes. In view 6, Bob (the next leader) goes offline, so the block doesn’t get finalized. When Carol becomes leader in view 7, MonadBFT requires her to include a Timeout Certificate (TC) and re-propose the highest-voted block from the previous view—Alice’s block.

If Carol doesn’t have Alice’s block, she asks the network. Validators either send the block or, if they don’t have it, respond with a signed No-Endorsement message. If enough validators lack the block, Carol can construct a No-Endorsement Certificate (NEC) to justify skipping it.

After re-proposing Alice’s block, Carol is also given an extra slot to ensure she’s not penalized for Bob’s failure. This reproposal mechanism ensures the chain progresses fairly, and no valid block is discarded due to faults or bad actors.

No-Endorsement Certificate (NEC)

As mentioned above, when a timeout occurs at Bob’s slot, Carol asks everyone for the high_tip block (Alice’s block), and at least 2f+1 validators will respond with either Alice’s block or with a signed No-Endorsement message.

If anyone responds with Alice’s block, Carol has the information and justification needed to re-propose it. Furthermore, Carol is expected to re-propose Alice’s block – the only way she is not allowed to is if at least f+1 people sign NE messages (allowing Carol to construct a No-Endorsement Certificate).

Why f+1? In any BFT system with 3f+1 validators, at most f can be malicious. If Alice’s block should persist, then at least 2f+1 honest nodes have received it. In order to skip Alice’s block and propose a new one at the same height, Carol needs f+1 validators to sign off on not receiving Alice’s block, but by assumption only f validators are Byzantine.

The NEC is the leader’s proof that skipping the reproposal is safe and justified. It is a receipt that says: “Here’s verifiable evidence that the previous block wasn’t ready to be finalized, so I’m not just ignoring it maliciously.”

Re-proposal + NEC = Tail Forking Resistance

To recap, combining re-proposal and NEC mechanism give MonadBFT a clear rulebook: either finalize what almost made it, or prove it wasn’t ready and move on. Nothing falls through the cracks.

This design guarantees tail-forking resistance: an honest leader’s block that garnered a supermajority of votes will eventually be committed. A leader cannot selfishly fork away their predecessor’s block without leaving a cryptographic trail because the absence of an NEC would expose them.

Economically, this protects validators: your block and rewards won’t be lost due to the next leader’s failure. Even if Bob skips his slot to help Carol steal Alice’s block, MonadBFT forces Carol to repropose Alice’s block first, nullifying any MEV gain.

The breakthrough here is that MonadBFT achieves this without heavy communication. Previous approaches to solve tail-forkings (like BeeGees) imposed quadratic communication in every round. MonadBFT relaxes those conditions by only invoking the broader communication (collecting lots of messages) when a failure happens, not every round. Thus, in the normal case of steady honest leaders, it still operates efficiently (more on happy vs unhappy path later).

Implications of MonadBFT for developers

So far, we examined how classic PBFT consensus works and how earlier versions of HotStuff operate. We also looked at how MonadBFT solves HotStuff’s tail-forking issue which is a problem where valid blocks sometimes get left behind in pipelined systems.

This tail-forking problem creates two big issues: 1) it messes up the rewards for honest block builders and 2) can potentially stall the network.

MonadBFT introduces Reproposal rule and No-Endorsement vote mechanisms to eliminate the tail-forking problem, ensuring that any properly approved block from an honest proposer will always make it into the chain.

In the following sections, we explore the other two characteristics of MonadBFT which are 1) speculative finality and 2) optimistic responsiveness. We will also explore the implications of MonadBFT for validators and developers.

One-round speculative finality

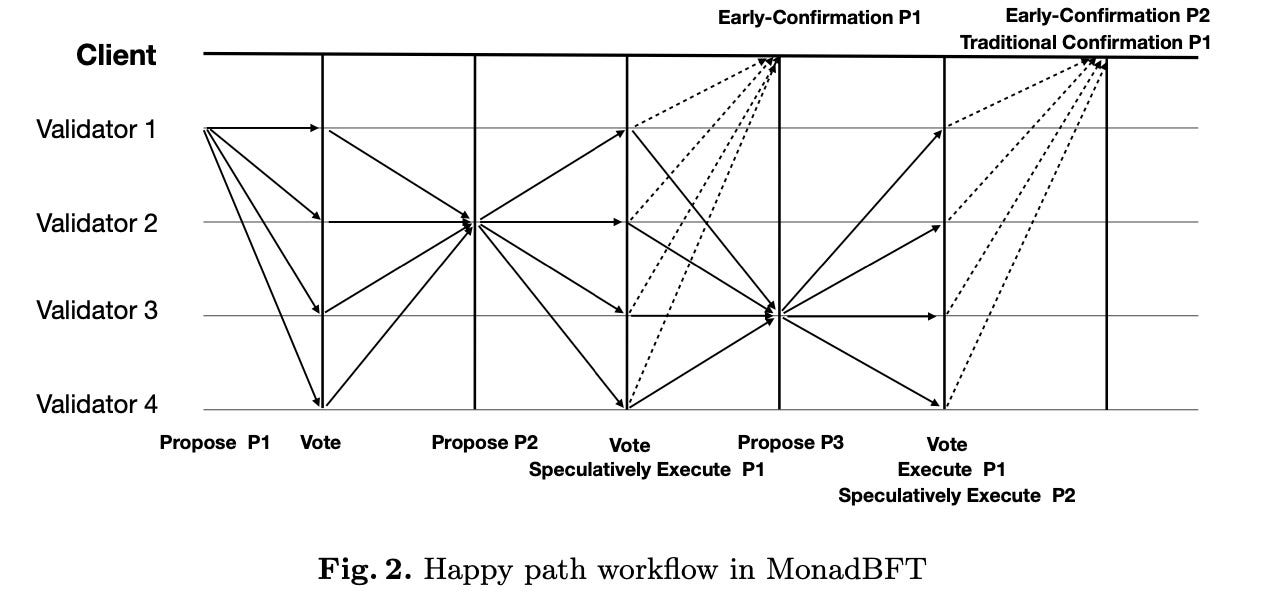

Besides tail-fork resistance, another major feature of MonadBFT is speculative finality within a single round.

In practical terms, this means clients can receive confirmation for their transaction immediately after a block gets a supermajority of votes, even before the next round completes.

Recall that in protocols like PBFT or baseline HotStuff, a block usually isn’t considered final (irreversible) until it has gone through at least two phases (e.g. Fast-Hotstuff & Diem-BFT): one phase to get a Quorum Certificate (lock the block with ≥2f+1 votes), and a second phase where the next leader builds on that QC and commits the block.

This two-phase commit is needed to ensure safety: once enough honest nodes have locked a block, no conflicting block can gather a quorum, and the commit in the next round makes it permanent. So normally, a client might have to wait for the next block or next round to be produced before they know the previous transaction is final.

MonadBFT basically allows a transaction to be considered final enough (safe to act on) after just one round of voting. This is called speculative finality.

When a leader proposes a block and the validators vote to form a QC for that block, that block is now in a Voted state (it’s locked by a quorum). In MonadBFT, validators will execute the block’s transactions as soon as they form the QC and even send a preliminary confirmation to clients indicating the block is (speculatively) accepted. This is like saying: “We have a supermajority agreeing on this block. Unless something very unexpected happens, consider this block confirmed.”

This immediate confirmation is optimistic. The block hasn’t been committed in the ledger yet. That will happen when the next proposal comes and finalizes it (QC-on QC), but under normal conditions, nothing will revoke it. The only scenario that can revert a speculatively executed block is if the leader equivocated (i.e. proposed two different blocks at the same height to split the vote).

You can think of speculative finality as a nice by-product of tail-forking resistance. The tail-forking resistance guarantees that even if the next leader crashes, the current proposal won’t be abandoned (thanks to reproposal and NEC rules). So the only time a speculatively executed block gets dropped is if the original proposer equivocated (double-signing fault that is provably malicious), which is: 1) detectable via conflicting QCs, 2) slashable and 3) extremely rare.

In previous protocols, they didn’t guarantee that the next leader would repropose the previous block, so tail-forking was possible, breaking speculation assumptions.

Optimistic Responsiveness

In most consensus protocols, there’s a built-in wait after each round like a buffer period or timeout. This is to make sure all messages have arrived before moving forward. It is a protective mechanism meant to handle the worst-case scenario like when a leader crashes or sends nothing at all.

These timeouts are often overly conservative. If the network is functioning normally and all validators are behaving correctly, that fixed wait becomes unnecessary overhead. Blocks could have been finalized faster, but the protocol held back just in case.

MonadBFT introduces optimistic responsiveness which means the protocol can advance immediately based on network messages, instead of always relying on fixed timers. The design principle here can be summarized as “fast when it can, patient when it must.” MonadBFT is designed such that in both the normal case and even in recovery from a fault, it does not pause for a predetermined timeout if it doesn’t have to.

In the happy path (means we have an honest leader): There is no built-in delay in proposing or voting. As soon as a leader has the turn, it proposes a block. As soon as validators receive a valid proposal, they vote. The moment the leader (or rather, the next leader, since votes go to the next proposer in pipelined HotStuff) collects 2f+1 votes, QC is formed and can be disseminated. In an optimistically responsive design, this triggers the next phase immediately.

In practice, this means if network latency between nodes is, say, 100ms, the consensus can potentially finish a round in just a couple of hundred milliseconds (plus computation and aggregation overhead). It doesn’t wait, for example, a full second “slot time” if it doesn’t need to. This is in contrast with Ethereum mainnet which follows a slot-and-epoch model [3]. On Ethereum, block production is fixed at 12-second intervals. Even if everyone is ready earlier, the protocol waits.

MonadBFT’s approach eliminates unnecessary delay. It retains the pipelined HotStuff structure but removes the rigid “you must wait Δ seconds” rule in the normal case. This means it can outperform time-bound systems in responsiveness without sacrificing safety.

In the unhappy path (leader failure): In many consensus protocols, when a leader fails to propose a block, other nodes only realize this after a timeout Δ has passed. If Δ is, for example, 1 second, that time is essentially lost. MonadBFT handles this differently. When validators detect a missing proposal, they immediately broadcast timeout messages (TC or Timeout Certificate). As soon as 2f+1 of these timeouts are seen, the next leader takes over. The transition to the new view is triggered by quorum-based evidence, not by the clock.

Comparison with hotstuff-family consensus

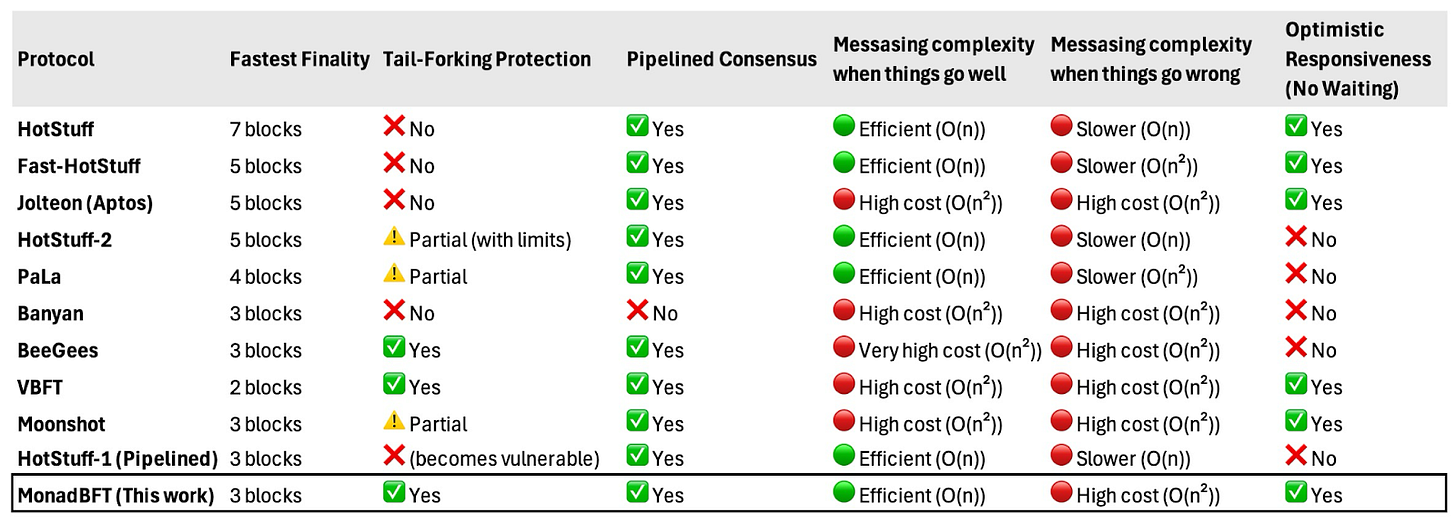

MonadBFT builds on the lineage of HotStuff-family consensus protocols, but stands out by achieving a combination of desirable properties that no previous design has been able to fully integrate without trade-offs.

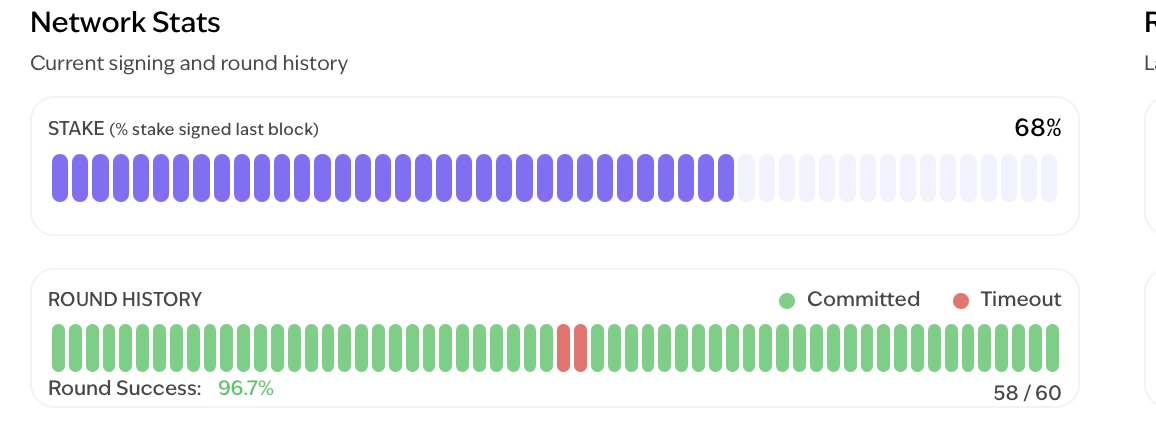

Earlier protocols were often optimized for some dimensions like pipelined throughput or linear communication but had to sacrifice others. MonadBFT uniquely manages to combine linear messaging complexity, pipelined commits, strong tail-forking resistance, instant responsiveness without fixed delays, and efficient recovery mechanisms, all while preserving fast finality and high liveness guarantees. The table below summarizes how MonadBFT compares to other rotating-leader BFT protocols across these critical dimensions:

What does this mean for Developers?

For Developers, MonadBFT means a couple of things:

Simpler Finality Model: With MonadBFT, you can treat a block that has a QC (supermajority vote) as effectively finalized for most purposes, because the protocol will finalize it or slash if not. Developers can safely act on 1-block confirmations with high confidence.

Improved UX for Apps: If you’re building a high-throughput application (exchange, game, etc.), MonadBFT’s low latency and fork-resistance translate to smoother UX. Users see their actions confirmed almost instantly and won’t commonly encounter confusing reorgs or rollbacks.

Deterministic Behavior: MonadBFT’s stricter rules (like reproposal requirement) reduce the non-determinism in block inclusion. There are fewer “corner-case” scenarios where a block might be included or skipped depending on subtle timing such as whether a vote or a timeout reached the leader first. MonadBFT replaces such ambiguity with explicit rules and verifiable evidence. This makes it easier to reason about the protocol’s correctness and to test it.

Scalability Headroom: If you are a developer concerned with scaling, MonadBFT gives you more headroom before hitting bottlenecks. And features like erasure-coded block dissemination [4] mean that you can push lots of data through the network without overtaxing individual nodes. This makes it possible to aim for higher throughput which opens up design space for more ambitious on-chain applications

For End-Users. A normie user won’t know about any of the stuff we discussed here, but they feel its effects. With MonadBFT underpinning Monad the chain, users can expect all the nice qualities below without sacrificing on decentralization and censorship resistance.

Faster Confirmations: Transactions (like sending tokens, swapping assets, minting NFTs, executing trades) will confirm very quickly.

Fewer Surprises: The consistency of the chain state is higher as stuff like tail-forking, which is an re-org essentially, gets eliminated

Fairness and Transparency: Improvements in consensus indirectly mean that the chain’s operation is fairer. No single validator can easily censor transactions or play games with ordering across blocks.

Conclusion

To recap, MonadBFT introduces four core innovations on top of pipelined HotStuff-style consensus:

Tail-Forking Resistance: MonadBFT is the first pipelined BFT protocol to eliminate tail-forking attacks by requiring the next leader to repropose the last voted block if the previous leader failed, or otherwise show a No-Endorsement Certificate (NEC) as proof that the block lacked support. This guarantees that no block endorsed by a supermajority will be abandoned, protecting honest leaders’ rewards and preventing malicious reorgs and cross-block MEV extraction.

Speculative Finality in One Round: Validators can confirm a block after a single round of communication (one leader proposal and votes), giving clients an immediate assurance of inclusion. This speculative confirmation will only revert if the leader equivocates (an act that can be proven and punished), making it a safe assumption in practice.

Optimistic Responsiveness: The protocol operates at network speed without inherent delays. Leaders advance the consensus as soon as the necessary votes are received, and view changes occur as soon as a quorum of timeouts is observed, rather than waiting for a fixed interval. This optimistically responsive design minimizes wait times, while still handling asynchrony and faults robustly when they occur.

Linear Communication: On the happy path (meaning leader is honest), message and authentication complexity is linear in the number of validators. MonadBFT retains HotStuff’s efficient communication pattern, using aggregated signatures and simple leader-to-validators broadcasts, which enables the protocol to scale to 100s of validators without performance bottlenecks.

Works Cited

Read the full MonadBFT Whitepaper here [5].

[1] https://pmg.csail.mit.edu/papers/osdi99.pdf

[2] https://arxiv.org/abs/2205.11652

[3] https://ethos.dev/beacon-chain

[4] https://www.category.xyz/blogs/raptorcast-designing-a-messaging-layer

[5] https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.20692

About the Author

Michael is an Ecosystem Associate at Monad Foundation. Prior to joining Monad, he worked as a strategy associate at a global cryptocurrency exchange. He also writes about crypto, economics, and policy. Connect with him on Twitter: @michael_lwy.